To be competitive in a “deregulated” market, power plant workers must be better qualified and more versatile than ever. Regardless of his or her area of expertise (operations, craft maintenance, plant controls, or other), tomorrow’s plant worker must be better skilled than ever before.

Regardless of plant design, fuel type, or loading schedules, the defining difference in plant performance resides in the people who operate, maintain, and manage the plant. Whether it’s how they respond to abnormal operating conditions, how conscientious they are with plant chemistry, or how well they test and maintain critical components; it’s people, not equipment that make the difference between a well run facility and one with never ceasing problems.

According to industry statistics, power generation facilities will loose between 30% and 50% of their most experienced workers over the next five years. This means that the people who hold the “tribal knowledge” of your facility will be leaving in the not too distant future. Furthermore, the availability of a trainable labor pool to replace the “Boomers” is in very short supply and difficult to recruit.

Introduction

There is no arguing that the power generation industry has changed significantly over the past two decades. There is also little doubt that the industry will continue to evolve as the process of deregulation moves forward. Most experts agree that within the next several years the majority electrical generation customers will be able to choose their power generation provider. This radical change from previous practices has caused power generation companies to transform themselves from stagnant monopolies into savvy business competitors.

As the de-regulation forces continue to increase, power companies have had to restructure their companies to become more competitive. One area of significant change involves improving the skills and abilities of the workers who operate and maintain the power generation facilities.

Throughout the 1990’s, many power companies tried to become more competitive by “downsizing” the workforce. However, having fewer workers at the plants has led to many additional challenges. For example, when the downsizing occurred, most plants found that their most experienced workers were the ones who left. This meant that the people who held the “tribal knowledge” were no longer available. In addition, many companies experienced a significant decrease in employee morale and union discontent when the downsizing was performed. The situation did not improve as companies increased their use of contract labor to accomplish the remaining work.

This article will overview how leading edge power generation companies have restructured their workforces to meet these competitive challenges. Present workforce case studies are included as well as “best practices” for the following goals:

- How to use technology-based training to lower workforce qualification costs

- How to create a “multi-skilled” workforce

- How to screen and hire top quality workers

Finally, this article provides guidelines on how each of these companies calculated the Return on Investment (ROI) for the actions they implemented. There are four levels of analysis that can be used to measure the effectiveness of a trainingrelated effort. Each one is listed below:

- Level 1 - Evaluate the trainees “reaction” to the training.

The traditional method of performing a Level 1 analysis is by administering “review sheets” at the end of a training session. These sheets are 1-2 page forms that ask a trainee how much they valued the training.

- Level 2 - Evaluate the skills and knowledge that were learned.

The traditional method of performing a Level 2 analysis is by administering pre- and post-tests to the trainees. If a significant increase is noted, the training is typically considered a success.

- Level 3 - Evaluate the “job application” of the skills and knowledge learned.

A Level 3 evaluation attempts to measure whether or not the training was “carried over” into the trainees work practices. This usually requires an objective evaluation to determine if the training modified employee job performance.

- Level 4 - Evaluate the “business results” of the skills and knowledge learned.

A Level 4 evaluation attempts to quantify the benefit that was “carried over” into the trainees work practices. This means that the training intervention must be at least partially responsible for results such as less accidents, improved productivity, lower downtime, or similar results. The Level 4 analysis compares the monetary value of the benefit obtained to the cost of the training intervention.

Calculating an ROI for any training intervention can be a very complicated exercise. The keys to success are (1) determining which performance indicators will be used to measure the training effectiveness, (2) establishing a “benchmark” for the indicators to be measured, and (3) preventing contamination of the data.

Case Study 1 - Using Technology-Based Training (TBT) to Lower Workforce Qualification Costs

This power generation Company operates approximately 24 fossil-fueled power plants over a relatively small geographical area. The Company operates an extremely broad range of power plant equipment (e.g. coal-, oil- and gasfired units, supercritical and conventional units, etc.). There are also several hydro plants located in the territory, as well as a few combined cycle plants. Since the Company was formed over 40 years ago, the workforce training practices have been ingrained over many decades. That strong reliance on classroom training and “buddytype” OJT had created many challenges for the Company.

In the early 1990’s “total training time” was a commonly used performance indicator for the technical training being provided at the various power plants. Little attention was paid to whether the training was really needed, and even less attention was paid to the effectiveness of training. In addition, duplication of courses was wasting significant resources. For example, the Company had identified 16 different versions of one classroom-training course that dealt with a single topic (confined space entry).

Before moving toward Technology-Based Training TBT), this power Company thoroughly analyzed its existing qualification programs. As a result, over 95% of a workers qualification was performed using the following techniques:

- Classroom instruction

- “Buddy-type” OJT

Classroom Instruction

The existing classroom instruction incorporated a wide variety of formats such as lectures, paper-based reading with an instructor, reviewing slides, and so forth. Once the analysis was completed, it was clear that the classroom training was very expensive when all costs were considered. The delivery costs for classroombased courses included, but were not necessarily limited to, the following:

- Instructor direct labor cost (preparation and course delivery time)

- Student direct labor cost (classroom and additional off-shift time related to the course)

- Instructor and student overhead cost (allocated based on direct labor costs)

- Instructor and student travel and living expenses

- Student replacement labor and/or overtime labor costs, including benefits and overhead

Miscellaneous expenses not included in overhead costs (e.g., course material printing costs)

In addition to the cost considerations, there were other factors that challenged the effectiveness of classroom training. Classroom training had been very difficult when all the trainees had different needs and goals. Another problem was scheduling considerations. Finally unless a top quality instructor was provided, the training results were often less than expected.

Buddy-type OJT

The Company’s OJT programs could be referred to as a “buddy type” system where a job incumbent trains the newly appointed individual for the job. There was little or no control over how or what the trainee is taught, or whether or not the trainer taught the correct techniques. If the trainer had no formal training or experience in administering OJT, the quality of the instruction was highly variable. Since there were no consistent, standardized, or objective evaluation techniques, there was no real way to monitor the training effectiveness. Generally, if the trainer employed bad techniques, these were passed on to the trainee. This type of OJT typically provides the hands on training of “how” things are done, but not “why” things are done that way.

OJT was typically performed as part of their Qualification Program and/or when a worker was assigned a task that he or she had not previously performed. As the worker completed the OJT task, the trainer (or Supervisor) observed the trainee to check job proficiency and knowledge. Even though many agree that OJT reinforced with some classroom training is an excellent way to train, “buddy-type” OJT alone was not an effective method to qualify their workforce.

Move to Technology-Based Training

In 1997, the Company aggressively turned toward “competency-based” or “performancebased” training. The Company also decided to implement the latest TBT approaches to (1) ensure that the training was more “self-directed”, and (2) to significantly lower overall training costs.

Competency-based training does not require a certain amount of training "seat time", but rather it focuses on the needed training outcomes. The goal is to ensure a person can understand and perform the specific job duties or tasks. Most of the training is provided in a self-paced or just-in-time format.

The core of this new approach involved the licensing of a computerized Learning Management System (LMS) that developed and delivered on-line examinations to individuals to assess their knowledge in specific areas. The software application included a large number of reports that can be used to monitor an individual’s performance and evaluate the validity of test questions included in the database. The system was installed across the entire Company using web-based technology.

The software program database was partitioned at the qualification program level. For example, a set of test questions were developed for a maintenance training assessment; and another set was developed and entered for a control room operator. Similar question sets were entered for fuel handling assessments, I&C technicians, and so on.

The LMS was also able to launch and track over 2000 individual web-based training (WBT) courses for all types of plant workers. In addition, each WBT program could be directly linked to “site specific” and/or “hands-on” training. For example, a Plant Mechanic can review a WBT course on Alignment, and then be required to demonstrate the process using the associated Qualification Card or Job Performance Measure (JPM). All records of both the WBT and the JPM were easily administered within this comprehensive software solution.

The setup of the LMS for each program area included specifying the following:

- The job positions covered by the program

- The lessons or modules included in the training program (these can also be defined as topics and/or activities covered in the training program)

- The learning objectives for the program

- The reference documents (and/or other reference materials) which serve as the source content for test question development. Typically, these references include training materials, procedures, industry codes and standards, regulatory requirements, and other similar source documents.

Even though WBT courses provide very costeffectively training, the Company did not eliminate classroom instruction. However, total classroom training time (and costs) was significantly reduced. Classroom instruction is still provided whenever:

- The topic demands a very effective method of transferring knowledge.

- An instructor is needed “real time” to answer questions.

- The topic demands an instructor to keep participants engaged.

- The instructor is needed to involve experienced participants in discussions to use their knowledge/experience to supplement and enhance classroom instruction.

Case Study 1 - ROI

The decision to implement this TBT program was evaluated in terms of its economic impact as well as many other factors. The decision process involved a comparative analysis of the delivery costs for the traditional classroom training courses and identification of the gross savings that were achieved as a result of the effort.

It was determined that "seat time" for self-paced courses was significantly less than for classroom-based training. The primary reason is the flexibility each student was able to move quickly through (or skip) material already known to the student, and to test out of the course whenever the student believes he or she is ready to do so. Well-written course materials also improved the efficiency of information transfer. Studies have shown that classroom-training time can be compressed, without a loss in effectiveness, by between 30% and 70% depending on a number of factors.

Implementing the self-paced, self-delivered training courses resulted in a 53% reduction in total training costs. Also, since the adult learners tend to be self-directed, the program was very well received within one year of implementation.

Case Study 2 - Creating a Multi-Skilled Workforce

One of the greatest areas of change in the power generation industry has been associated with multi-skilling and cross-training of the workforce. The following paragraphs summarize how one Company implemented a multiskilled workforce to become more competitive.

The Company operates a wide range of power plant equipment (e.g. coal, oil- and gas-fired units, hydro units, and combined cycle plants). Since the Company was formed by combining several smaller utilities, the workforce is represented by several different labor unions. This diverse workforce has created many challenges for the Company.

In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, this power Company began to benchmark the workforce staffing at IPP’s and co-generation companies. For example, a 500 MW gas turbine based plant with DCS controls could be effectively operated by 20-35 people. Right or wrong, one outcome of the benchmarking was that this Company decided to downsize their workforce by approximately 45% in the mid 1990’s. At certain plants, the employee reductions were larger than 50% (e.g. the workforce at a 1600 MW coalfired station with scrubbers went from 280 employees to about 130). Unfortunately, the employees who left the Company were often the more senior and experienced workers who took a “severance package.”

After the downsizing, the traditional ways of having only one skill set for each individual employee was no longer adequate. As part of this strategy, management realized that the remaining workers would have to be more versatile than ever. Regardless of his or her area of expertise (operations, maintenance, or other), the worker at this Company must be able to competently perform several jobs. As with most efforts that involve “change”, a significant amount of training would be needed to achieve this goal.

The Company began an aggressive “cross-training” program in the mid-1990’s. The Company’s multi-skilling effort involves a standard curriculum of WBT courses that is supplemented by structured OJT. The specific WBT courses provided were determined internally using a modified Job and Task Analysis. The structured OJT exercises were also developed internally.

Both standard and customized exams are used to determine if an individual employee has successfully completed the required cross-training. Written exams are used to determine that an employee has the required "knowledge" of the proposed subject matter. Performance exams are used to determine if the employee can perform the required “skill” for the given task. Combining both written exams and structured OJT has been very important to the programs success.

The Company gave workers a financial incentive to learn “secondary” skills in addition to their primary classification. For example, an outside equipment operator could increase his or her pay by becoming qualified in any of the following areas:

- Mechanical Maintenance

- Electrical Maintenance

- Instrumentation and Control

- Fuel Handling

The goal was to create a flexible “plant worker” who could perform several duties in different areas of the plant. The Company is using a “pay-for-skills” approach to the crosstraining effort. Each individual has a pre-set curriculum that outlines the cross-training goals. When the certain goals are achieved, the employee’s salary is increased. An employee typically “tops out” at the highest pay level after 3-4 years in the program. At that point, refresher training is provided to ensure that adequate skill sets are maintained. A comprehensive Learning Management System (LMS) was also purchased and installed to track the qualification process for several thousand employees.

Case Study 2 - ROI

The decision to implement a self-paced, crosstraining program was primarily related to worker flexibility and scheduling. Almost everyone can agree that qualifying a mechanic to “disconnect motor leads” has an economic benefit to the Company. In addition, most workers will agree that having an electrician perform this type of routine task is not an effective use of resources.

The Company performed a comparative analysis of the many factors that influenced the success of the multi-skilling effort. Overtime costs, training costs, workforce reductions, and many other factors were included in the analysis. Benefits attributed to the multi-skilling effort included lower maintenance costs, reduced training costs, and outstanding operating records for the plants. The reduction in employee overtime was also significant. To date, the program has been considered very successful. Estimated productivity increases have saved Company millions of dollars annually.

Case Study 3 - Hiring and Screening

Why do some power plants run more efficiently than others? How can a given power plant be competitive in a deregulated market? Regardless of design, fuel type, or loading schedules, the defining difference lies in the people who operate, maintain, and manage the plant. To a large extent, assembling a well-qualified work force begins with the hiring and screening process.

This power generation Company is an industry leader that began purchasing and operating power plants in the early 1980’s. Since that time, they have developed a portfolio of units that includes virtually all types of equipment across the United States. The balance of plant types is evenly distributed between conventional steam units, and gas turbine based plants (both simple and combined cycle). Collective bargaining units represent the workforce at the majority of these locations.

Since the Company began operating as an IPP, it maintained a very lean workforce across its various units. The conventional units have all been staffed with very small crews, and the combined cycle plants were even leaner. The staffing levels for this Company have been used by several other power generation firms for benchmarking purposes.

For the older plants, cross-training was a significant part of a workers qualification process. Each site was staffed with a Plant Manager who had aggressive criteria for the skills and abilities of each worker. New hires were recruited from existing power stations, and then trained “on-thejob” by more experienced (and more flexible) employees. For example, all Plant Operators were trained how to diagnose and troubleshoot both electrical and I&C problems. The Operators were also required to make certain mechanical repairs and adjustments to equipment during “off-peak” work times. Almost all training for this Company was budgeted at the plant level, and implemented locally as well.

In the late 1990’s, the Company had faced a significant challenge in hiring and training new workers. With so many new plants being built, a large percentage of its experienced workers were hired away. Accordingly, the Company took a hard look at the best hiring practices to fill these new positions. Initially, the new hires were experienced workers that came from other locations. However, more recently the Company has had to hire workers without a significant background in the power generation industry.

This Company developed a rigorous candidate screening process to help identify which potential employees had the greatest chance for success. Many resources were used to accomplish the following staffing objectives:

- Develop an accurate and flexible hiring process that can be used consistently across the organization.

- Ensure that every employee meets the competencies required for success.

- Reduce time to hire by providing immediate applicant contact, assessment, interviewing and follow-up.

- Reduce Human Resources and hiring managers’ time in interviews by using powerful pre-screening tools.

- Eliminate unnecessary monetary and time expenditures on un-qualified and less-qualified applicants.

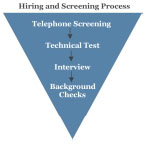

The following four step process was used for the hiring of workers.

Step 1 - Telephone Screening

Although numerous methods were used to recruit candidates, all candidates were first directed to a dedicated toll free hiring line where the following activities occurred:

- Their application information was entered into a candidate tracking system. This system was installed on-site and updated regularly.

- Candidates were given a basic overview of the job and asked basic screening questions about legal requirements to work, hours available, pay and expectations. They were asked where they heard about the opening, and this helped the Company track the success of the various recruitment campaigns.

- If a given candidate met the applicant screening criteria, they were scheduled to participate in the on-site hiring process. Candidates who did not meet screening criteria were mailed regrets letters.

Step 2 – Technical Tests

Candidates who successfully passed the telephone-screening phase were invited to the staffing center (set up locally) to participate in the computerized testing phase of the hiring process. The initial tests were tailored to assess such things as attention to detail, process monitoring, problem solving, teamwork, attitude, and personality characteristics. The results were summarized quickly, which allowed successful candidates to be progressed on to the next phase on the same day.

The second set of tests were designed to evaluate technical competencies. Different exams were created based upon the job being interviewed for. These computerized, multiple-choice tests were designed to assess basic mechanical aptitude (all positions), operations skills (operator positions) and technical skills (maintenance positions). All candidate data was scored, stored and tracked via the computer.

Step 3 – Interview

Following the computer based testing, successful candidates were interviewed. These structured interviews contained motivational, behavioral and situational items. The structured interviews were designed to determine work related interests and job experience, as well as Teamwork, Attitude, Initiative, Safety, Situational Responses, Leadership Qualities, Adaptability, and Personal Characteristics.

Step 4 – Background Checks

Successful candidates had their employment, educational and criminal history investigated. This process helped to verify information, which the candidates provided on their resume or in the interviews. It also served as an additional job fit measure. In addition, candidates were submitted to an intoxicant screen and a physical to determine job fitness.

With the benefits of automation, final interviews and conditional job offers can occur on the same day as the in-depth assessments outlined in Steps 2 and 3 outlined above.

Case Study 3 - ROI

The economic impact of the improved hiring and screening process was calculated by the Company, and the results were very impressive. An extremely high percentage of those who passed the screening process remained with the Company as highly productive workers.

During the ROI evaluation, it was observed that the personnel hired with a maintenance background, in general, were more successful in developing the overall skills and knowledge necessary to operate at a combined cycle facility. In other words, it was easier for a maintenance person to learn operations, than for an operations worker to learn the maintenance skills. A much higher percentage of new hires with an operations background were not able to make the cut, than

those with a maintenance background.

Since observing these results in the earlier built plants, the Company has focused its hiring practices on personnel with a maintenance background. The required training is focused more on operations, and much of the curriculum is self-paced. This practice has shortened the training time for the new hires at the newer combined cycle facilities.

Conclusions

The case studies cited above overview how selected power generation companies have approached the workforce challenges that presently exist. There are other companies that have approached these issues differently with varying degrees of success. However, the examples cited are representative of many power companies.

To be competitive in a “deregulated” utility market, the power plant worker must be more highly skilled than ever. Regardless of the workers traditional area of expertise (production, transmission, or distribution), the leading edge power companies are now requiring broader sets of skills for each and every employee. The challenge is to create a qualified workforce that provides a true ROI to the workers and the Company, and is consistent with the business realities and culture at your facilities.

Russ Garrity, can be reached at:

General Physics Corporation

e-mail: rgarrity@genphysics.com

or visit: www.energywbt.com